Lifespan vs Healthspan: Why Omega-3s Matter Early—and Always.

You might want to extend your lifespan, but it’s your healthspan—the years lived in good health—that truly determines quality of life.^1 Omega-3 fatty acids are central to that pursuit. The omega-3 “family” includes the parent essential fatty acid alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) and the long-chain omega-3s EPA, DHA, and DPA found “ready-made” in fish.^2,3 These fats are structural components of cell membranes and play vital roles in the eyes, brain, immune, and circulatory systems.^2 While ALA can convert to EPA/DHA, conversion is low (<20%), so getting a variety of omega-3s from diet and/or supplementation is important.^3

How Much Omega-3? Intake Guidelines & Food Sources

Adequate Intakes (AIs) for omega-3s (ALA) vary by age/sex (men 1.6 g/day; women 1.1 g/day; higher in pregnancy/lactation).^2 The WHO suggests EPA+DHA in the 0.25–2 g/day range, with fish consumption 1–2 servings/week (≈200–500 mg EPA+DHA per serving), and some organizations recommending up to 3 g/day.^4

Common sources include fatty fish (e.g., salmon, mackerel, trout) for EPA/DHA and plant foods (e.g., chia, flax, canola oil) for ALA.^2

The Omega-6 : Omega-3 Ratio—Balance the Inflammation Equation

Western diets are typically high in omega-6 and low in omega-3, a pattern associated with a pro-inflammatory state and weight gain in animal/human data.^5 Because the body can’t interconvert omega-6 and omega-3 families, improving the omega-6 : omega-3 ratio means reducing excess omega-6 and raising omega-3 intake.^5

Growing Strong: Pregnancy, Infancy & Childhood.

Omega-3s concentrate in the developing brain and retina; DHA is especially critical for normal eyesight and brain function in infants.^3,6 Maternal intake directly impacts fetal omega-3 status, and guidance suggests 225–340 g seafood/week during pregnancy/lactation (2015–2020 DGA).^3,7 Supplementation trials (≈2.5 g/day omega-3s) during pregnancy/lactation show benefits for children’s mental processing and problem-solving, with reductions in maternal inflammation.^3,8 Additional observational work linked low maternal EPA+DHA with a 10× higher risk of early preterm birth vs. higher EPA+DHA.^9

During childhood/adolescence, intakes of long-chain omega-3s are often low (e.g., <300 mg/day vs. ≥500 mg/day suggested in some cohorts).^10 Meta-analysis suggests omega-3 supplementation may improve ADHD symptom scores and attention-related cognition in youths with lower omega-3 status.^11 Nutrition literacy is also a gap: although most teens know fish is “healthy,” relatively few eat it regularly, and only 36% know how much omega-3 they need.^12

Teens to Adulthood: Inflammation, Pain, and Performance

Higher omega-6 and lower omega-3 can increase uterine inflammation and dysmenorrhea symptoms; omega-3 supplementation has been shown to reduce menstrual pain in adolescents.^13

As adults, chronic low-grade inflammation underlies many degenerative conditions (CVD, type 2 diabetes, some cancers).^14 EPA and DHA down-regulate pro-inflammatory genes, reduce CRP, and help modulate atherosclerotic processes.^3

Ageing Well: Muscle, Mind, and “Inflamm-aging”

Ageing is accompanied by declines in memory, muscle, bone, vision, hearing, and skin integrity.^15 Persistent inflammation accelerates this “inflamm-aging” trajectory, contributing to osteoporosis, Alzheimer’s, depression, and CHD.^16,17

In older adults, higher-dose EPA/DHA (e.g., 1.86 g EPA + 1.5 g DHA/day, 8 weeks) favorably influenced muscle protein turnover, helping counter sarcopenia.^19 Yet only ~24% of older adults meet ≥500 mg/day EPA+DHA (ISSFAL standard) in some datasets.^20 Broad evidence supports omega-3 roles across cognition, bone, muscle, immune, and cardiovascular health in ageing.^21

The Omega-3 Index: A Practical Biomarker

The Omega-3 Index measures EPA+DHA in red blood cell membranes (% of total fatty acids). An Index >8% is associated with lower CHD risk, while <4% is highest risk.^22,23 Raising the Index is linked with improvements in blood pressure, triglycerides, and inflammatory markers.^24 Lifestyle factors (age, education, fish intake) and risks (waist circumference, smoking) influence Index values, with lower national intakes reported in the U.S., Canada, Brazil, India compared with Japan, South Korea, Iceland, Mediterranean, Pacific Island regions.^25–27

Human Clinical Trials.

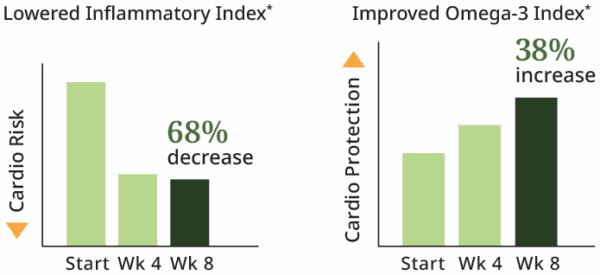

A human study on Omega-3 Plus showed:

- +38% Omega-3 Index after 8 weeks (from 6.2% → 8.5%, into the “low-risk” zone).^18,22

- −68% inflammatory index after 8 weeks.^18

The formulation provides a complete spectrum of eight nutritionally important omega-3 fatty acids, including ≈460 mg EPA and ≈480 mg DHA per serving.* These findings have been presented at major scientific meetings (e.g., American College of Nutrition).^18

Key Takeaways

- Healthspan > Lifespan: Omega-3s support cellular structure/function throughout life.^1–4

- Balance the ratio: Improve the omega-6 : omega-3 balance to reduce pro-inflammatory tone.^5

- Start early: Omega-3s are crucial from pregnancy through adolescence for brain/eye development and behavior.^3,6–13

- Age smart: EPA/DHA help counter inflamm-aging, support muscle, cardio-metabolic, and cognitive health.^14,16–21

- Measure what matters: Track EPA+DHA via the Omega-3 Index and aim for >8%.^22–24

- Evidence you can use: NeoLife’s clinical data demonstrate meaningful changes in Omega-3 Index and inflammation markers in 8 weeks.*^18

💬 Keep Learning

- 🧠 Omega-3 and Mental Wellness: How Nutrition, Movement, and Mindset Strengthen the Brain

Discover how daily movement, nutrient density, and cellular balance shape emotional resilience.

References:

- Crimmins EM. Gerontologist. 2015;55(6):901-911.

- NIH ODS: Omega-3 Fatty Acids.

- Swanson D, et al. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(1):1-7.

- FAO/WHO. Fats and Fatty Acids in Human Nutrition. 2010.

- Simopoulos AP. Nutrients. 2016;8(3):128.

- Birch DG, et al. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(8):2365-2376.

- US HHS/USDA. 2015–2020 DGA.

- Helland IB, et al. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e39-e44.

- Olsen SF, et al. EBioMedicine. 2018.

- Gopinath B, et al. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2).

- Chang JP-C, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(3):534-545.

- Harel Z, et al. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28(1):10-15.

- Harel Z, et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(4):1335-1338.

- Hunter P. EMBO Rep. 2012;13(11):968-970.

- NIH MedlinePlus Magazine (Winter 2007).

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, et al. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(6):988-995.

- Walston JD. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(6):623-627.

- Carughi A. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008.

- Smith GI, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(2):402-412.

- Sheppard KW, Cheatham CL. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17(1):43.

- Molfino A, et al. Nutrients. 2014;6(10):4058-4072.

- Harris WS, von Schacky C. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):212-220.

- Harris WS. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2009;11(6):411.

- Schacky C, Clemens. Nutrients. 2014;6(2):799-814.

- Wagner A, et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015;69(4):436-441.

- Langlois K, Ratnayake WMN. Health Rep. 2015;26(11):3-11.

- Stark KD, et al. Prog Lipid Res. 2016;63:132-152.